, 5 min read

Precision, recall and why you shouldn´t crank up the warnings to 11

Recently, the code hosting site GitHub deployed widely a tool called CodeQL with rather agressive settings. It does static analysis on the code and it attempts to flag problems. I use the phrase “static analysis” to refer to an analysis that does not run the code. Static analysis is limited: it can identify a range of actual bugs, but it tends also to catch false positives: code patterns that it thinks are bugs but aren’t.

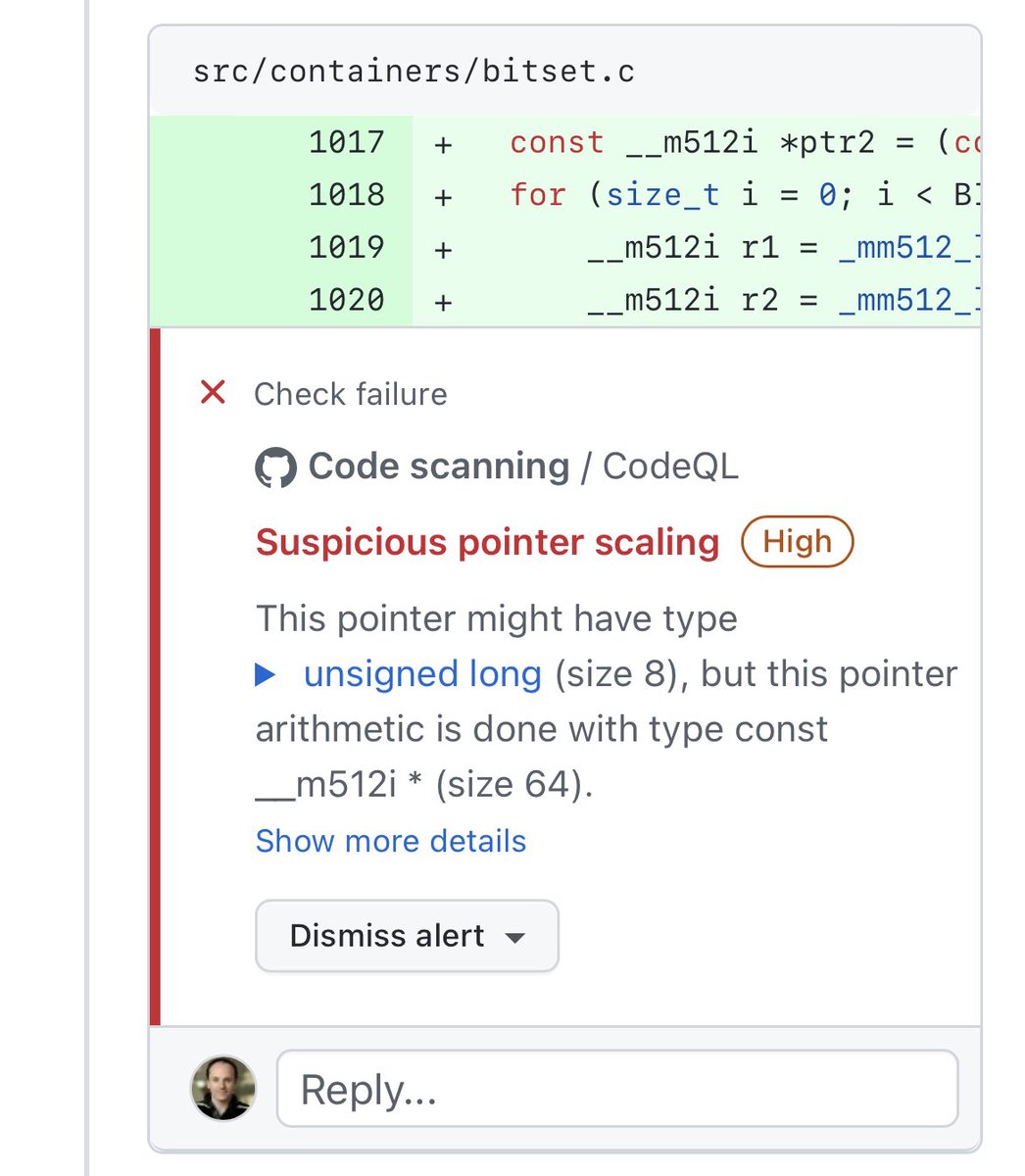

Several Intel engineers proposed code to add AVX-512 support to a library I help support. We got the following scary warnings:

CodeQL is complaining that we are taking as an input a pointer to 8-byte words, and treating it if it were a pointer to 64-byte words. If you work with AVX-512, and are providing optimized replacements for existing function, such code is standard. And no compiler that I know of, even at the most extreme settings, will ever issue a warning, let alone a scary “High severity Check Failure”.

On its own, this is merely a small annoyance that I can ignore. However, I fear that it is part of a larger trend where people come to rely more or more on overbearing static analysis to judge code quality. The more warnings, the better, they think.

And indeed, surely, the more warnings that a linter/checker can generate, the better it is ?

No. It is incorrect for several reasons:

- Warnings and false errors may consume considerable programmer time. You may say ‘ignore them’ but even if you do, others will be exposed to the same warnings and they will be tempted to either try to fix your code, or to report the issue to you. Thus, unless you work strictly alone or in a closed group, it is difficult to escape the time sink.

- Training young programmers to avoid non-issues may make them less productive. The two most important features of software are (in order): correctness (whether it does what you say it does) and performance (whether it is efficient). Fixing shallow warnings is easy work, but it often does not contribute to either correctness (i.e., it does not fix bugs) nor does it make the code any faster. You may feel productive, and it may look like you are changing much code, but what are you gaining?

- Modifying code to fix a non-issue has a non-zero chance of introducing a real bug. If you have code that has been running in production for a long time, without error… trying to “fix it” (when it is not broken) may actually break it. You should be conservative about fixing code without strong evidence that there is a real issue. Your default behaviour should be to refuse to change the code unless you can see the benefits. There are exceptions but almost all code changes should either fix a real bug, introduce a new feature or improve the performance.

- When programming, you need to clear your mental space. Distractions are bad. They make you dumber. So your programming environment should not have unnecessary features.

Let us use some mathematics. Suppose that my code has bugs, and that a static checker has some probability of catching a bug each time it issues a warning. In my experience, this probability can be low… but the exact percentage is not important to the big picture. Let me use a reasonable model. Given B bugs per 1000 lines the probability that my warning has caught a bug follows a logistic functions, say 1/(1+exp(10 – B)). So if I have 10 bugs per 1000 lines of code, then each warning has a 50% probability of being useful. It is quite optimistic.

The recall is how many of the bugs I have caught. If I have 20 bugs in my code per 1000 lines, then having a million warnings will almost ensure that all bugs are caught. But the human beings would need to do a lot of work.

So given B, how many warnings should I issue? Of course, in the real world I do not know B, and I do not know that the usefulness of the warnings follows a logistic function, but humour me.

A reasonable answer is that we want to maximize the F-score: the harmonic mean between the precision and the recall.

I hastily coded a model in Python, where I vary the number of warnings. The recall always increases while the precision always fall. The F-score follows a model distribution: having no warnings in terrible, but having too many is just as bad. With a small number of warnings, you can maximize the F-score.

A more intuitive description of the issue is that the more warnings you produce, the more likely you are to waste programmer time. You are also more likely to catch bugs. One is negative, one is positive. There is a trade-off. When there is a trade-off, you need to seek the sweet middle point.

The trend toward an ever increasing number of warnings does not improve productivity. In fact, at the margin, disabling the warnings entirely might be just as productive as having the warnings: the analysis has zero value.

I hope that it is not a symptom of a larger trend where programming becomes bureaucratic. Software programming is one of the key industry where productivity has been fantastic and where we have been able to innovate at great speed.